By Edith Hathaway ©2017

By Edith Hathaway ©2017

There are cultural flashpoints in every era. And since musical tastes typically take the longest to develop, flashpoints may be recognized at the time as such. But they can also take many more decades before their impact is fully understood. One such moment was on Feb. 12, 1924 at a concert in New York City, now referred to as “a defining event of the Jazz Age and the cultural history of New York City.” (Wikipedia: Aeolian Hall) The concert became known as a “jazz concert” only years after the event. It was also the world premiere of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. Up to that time, Gershwin was largely unknown to the classical music world.

In late 1923 Paul Whiteman (“King of Jazz”) announced he would present a concert called “An Experiment in Modern Music” in New York City. Paul Whiteman and his Palais Royal Orchestra were the best known and most successful dance band of the 1920s. Whiteman’s musicians were both highly accomplished and versatile, each of them often playing several instruments. He preferred classically trained musicians, with an average of 12 and up to 35 of them in his group. Whiteman offered them four times the salary they made with a symphony orchestra, even in prestigious positions. Some were gifted arrangers and orchestrators who could exploit the virtuosity of the group. Among them was composer/pianist Ferde Grofé. When Gershwin was commissioned to compose a new piece for piano and jazz band for the Feb. 1924 concert, it was Grofé who orchestrated Rhapsody in Blue.

Gershwin worked on ideas for the piece in late Dec. 1923, including on a train trip to Boston, where previews were held for the show, Sweet Little Devil, for which he had written the music and Buddy DeSylva the lyrics. The show was in final rehearsals and set to open on Broadway Jan. 21, 1924. According to some accounts, Gershwin was so occupied with that production that he had forgotten about the Whiteman commission until his brother Ira spotted an announcement of the concert in The New York Tribune, Jan. 4, 1924. Ira, George, and Buddy DeSylva were relaxing in a billiards parlor at the time when Ira read it aloud. The final paragraph surprised Ira: “George Gershwin is at work on a jazz concerto, Irving Berlin is writing a syncopated tone poem and Victor Herbert is working on an American suite.”

Gershwin started notating the original score on Jan. 7th and completed it in three short weeks, leaving little time for orchestrating the 16-minute piece. Grofé made daily trips to the Gershwin household to gather pages, and completed the orchestration just eight days prior to the concert. He scored the piece for an expanded Palais Royal Orchestra of 23 musicians plus solo piano (Gershwin), with many musicians doubling on numerous instruments. He later did orchestrations of Rhapsody in Blue for larger orchestras (1926 and 1942).

The full concert consisted of 26 individual segments by leading jazz and classical composers, including Gershwin. Whiteman said it would be a largely educational concert – especially to determine what was American music; and to challenge the notion that jazz music had no place in the concert hall, since up to then jazz music was known strictly as dance music. To prove the point, Whiteman booked one of the premiere classical music concert halls in New York City. The Aeolian Hall was normally home to the New York Symphony and its conductor Walter Damrosch. Whiteman invited many distinguished guests from across the cultural spectrum. Among them were pianist/composers Sergei Rachmaninoff and Leopold Godowsky, composers Igor Stravinsky, Ernest Bloch and John Phillip Sousa, violinists Jascha Heifetz and Fritz Kreisler, conductors Walter Damrosch and Leopold Stokowski, actress Gertrude Lawrence, and dancers Fred and Adele Astaire. Many people at the time thought it was a preposterous idea to bring together jazz, popular music, and concert music in the same program. In the U.S. this was still an unconventional and novel combination, frowned on by most arbiters of good taste in the classical music world: music critics, composers, and music conservatory stalwarts. But American jazz was beginning to interest and inspire some composers in Europe (including Maurice Ravel and Béla Bartók, who were Gershwin fans); and Whiteman had an excellent sense for what would interest and excite the public. Jazz afficionados in the U.S. were further emboldened by the concert, especially as it was scheduled for Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. They called it “The Emancipation Proclamation of JAZZ.”

“… If I’d been willing to wait a few centuries for a verdict on my work, I wouldn’t have been so wrought up over the Aeolian Hall concert. But here I saw the common people of America taking all the jazz they could get and mad to get more, yet not having the courage to admit that they took it seriously. I believed that jazz was beginning a new movement in the world’s art of music. I wanted it to be recognized as such. I knew it never would be in my lifetime until the recognized authorities on music gave it their approval.” Paul Whiteman, excerpt from his 1926 autobiography Jazz, with co-author Mary Margaret McBride.

Click here for a brief review on how to read the South Indian charts.

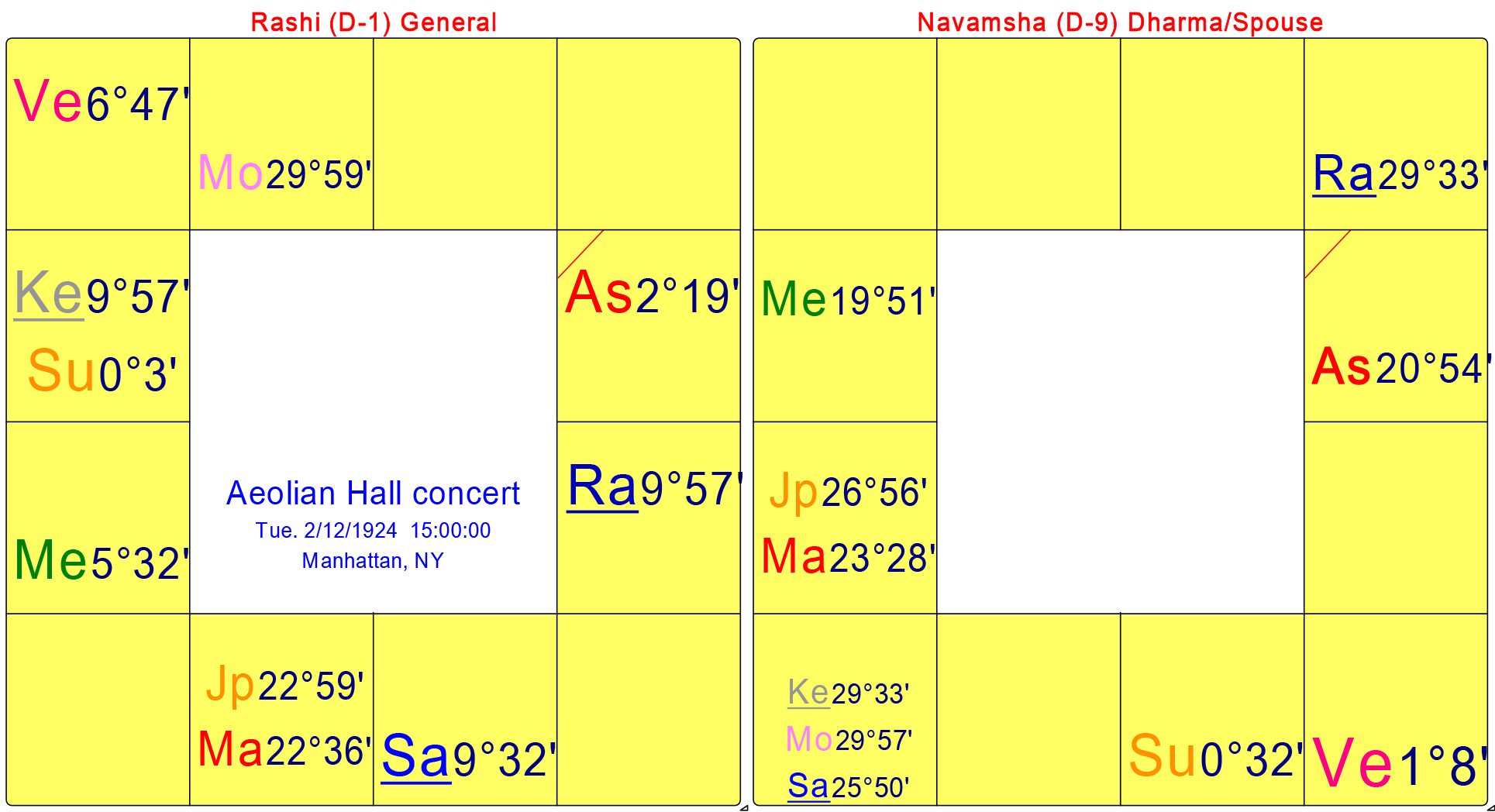

SOURCE: http://bixbeiderbecke.com/ReviewRecreationAeolianHallConcert.html The cover of the original concert program is shown, with date and time given: Feb. 12, 1924, 3 pm, Aeolian Hall, New York City. The hall seated 1100 people and they were fighting to get in the door on a cold, snowy day. Hundreds of people were turned away at the box office. In her 1993 biography, The Memory of All That: The Life of George Gershwin (p. 83), author Joan Peyser says the concert began at 2:45 pm (29:17 sidereal Gemini Ascendant). But this is unlikely, in my opinion, especially as the original concert program confirms the start time was 3:00 pm, and many people were vying to get in the hall. Paul Whiteman writes in his 1926 autobiography, Jazz, that he delayed starting the concert for a short time while he dealt with his anxieties of taking on such a major project, and with all the distinguished artists and patrons in the audience, many of whom he had personally invited. He writes that he slipped out of the hall to check on the box office: “There I gazed upon a picture that should have imparted new vigor to my wilting confidence. It was snowing, but men and women were fighting to get into the door, pulling and mauling each other as they do sometimes at a baseball game or a prize fight, or in the subway. Such was the state of my mind by this time that I wondered if I had come to the right entrance. And then I saw Victor Herbert going in. It was the right entrance, sure enough, and the next day the ticket office people said they could have sold out the house ten times over.” (Paul Whiteman quoted in Gershwin: A Biography, 1987, by Edward Jablonski, pp. 68-69)

THE CONCERT – WHAT THE PLANETS TELL US

Watery planets, along with a watery Ascendant lend themselves to a musical event, but to have a musically stunning, even historical event, the chart should have the strong influence of the classical benefic planets: Venus and Jupiter. At 3:00 pm there is a watery Ascendant (Cancer) as well as three planets in water (Mars and Jupiter in Scorpio, and Venus in Pisces). Music is especially linked with the watery element, as it connects people to their emotions and memories (Moon), and has a potentially transformative effect.

Moon has the ability to connect with all things and all people. As Ascendant lord, Moon is in the 10th house at 29:59 Aries, and at 3:01 pm it shifts into Taurus, its sign of exaltation. The Moon gains strength here in two ways. At 3:00 pm tr. Moon is in a kendra (angular house) at the highest degree of celestial longitude, giving it Atmakaraka status. The Atmakaraka planet has power in the chart, especially as Ascendant lord. Once tr. Moon shifts into Taurus, it resides in its sign of exaltation, which is further empowered due to its sign lord Venus in turn being also exalted. Venus rules over music and the arts, and the Moon rules over the people, the public, and the receptivity to emotional and/or mental content. Once tr. Moon shifts into Taurus at 3:01 pm, it is undoubtedly within the time period when the concert actually began, according to Whiteman’s autobiography. We then have three planets in exaltation, the first two being classical benefic planets: waxing Moon in Taurus, Venus in Pisces, and Saturn in Libra. But the Moon about to change signs so quickly telegraphs the message of a shift that occurs during this concert, or perhaps even because of this concert.

Both Moon and Saturn reside in signs ruled by exalted Venus, ruler of music. Venus in turn is situated in the auspicious 9th house from the Ascendant. Further, Saturn has added strength being at its exact Stationary Retrograde (SR) degree, having turned SR two days earlier at 9:32 Libra. This feature contributed to the longevity of the concert program itself, whose conception was so successful that Whiteman gave seven more “Experiments in Music” concerts, the last one in 1938. A strong Saturn also helped to compensate for the speed at which everyone was working, especially in order to bring Rhapsody in Blue to the concert stage for its world premiere performance. With Mars losing the Graha Yuddha (Planetary War), and a Total lunar eclipse coming 8 days after the concert at 7:58 Leo, within two degrees of Rahu in the concert chart, it would have been easy for many components to spin out of control, including Gershwin completing the work at all, or the musicians not having enough time to rehearse it. But Ferde Grofé, among others, worked with discipline and precision to scrupulously honor Gershwin’s intentions. Tr. Mars is also greatly modified here by tr. Jupiter, as we shall see.

The Cancer Ascendant is reinforced 1) by being in its Vargottama segment (repeats in the Navamsha chart), 2) by receiving benefic Jupiter’s aspect, and 3) by having a strong Ascendant lord (Moon). Cancer as the 4th astrological sign naturally rules over classic 4th house matters, which include family, home, and education. Paul Whiteman grew up in Denver, Colorado, where his father was supervisor of music in the Denver public schools for 50 years and his mother, a former opera singer, sang in choral societies. His music education was rigorous; he played violin and viola in classical orchestras in Denver and San Francisco before moving into the jazz medium, which in the 1910-1920 era was still in its infancy in the U.S. Inheriting some of his father’s pedagogical skills, and with his own publicity instincts, Whiteman billed this concert as “an educational concert.” He included an expensive 14 pages of educational material within the Feb. 12, 1924 concert program, and hired a narrator to introduce each piece. He also invited some of the most esteemed New York music critics.

Tr. Mars and Jupiter are in Graha Yuddha (Planetary War) on a Tuesday, a Mars-ruled day. Normally Mars would be crushed by Jupiter, but because these are two great good planetary friends and both of them Raja yogakarakas for Cancer Ascendant (Jupiter rules the 9th house, a trinal house; Mars the 10th house, an angular house), Mars does not do badly. Mars and Jupiter together produce a Maha Raja yoga in the 5th house: a Dharma Karmadhipati yoga. This is exceedingly fortunate for matters of career and status. When tr. Moon moves into Taurus at 3:01 pm, tr. Jupiter and Mars also become Atmakaraka and Amatyakaraka planets respectively, giving them Jaimini Raja yoga status. (Again, Atmakaraka is the planet at the highest degree of celestial longitude, and Amatyakaraka is the next highest degree of celestial longitude.)

Since the Cancer Ascendant is Vargottama, (repeats in the Navamsha), this auspicious yoga appears again in the Navamsha chart, this time in the 7th house in Capricorn. This is also a Neecha Bhanga Raja yoga, since Navamsha Jupiter is debilitated in Capricorn, but is corrected by its contact with exalted Mars also in Capricorn. In both the birth chart of the concert and in the Navamsha we see how a potential defeat is turned into a triumph. The 10th house lord (Mars) is lifted up by Jupiter in the birth chart, and in the Navamsha chart the 9th house lord (Jupiter) is lifted up by exalted Mars (10th house lord). The concert is on a Mars-ruled day, Mars is in its own sign, and though Jupiter defeats Mars in the Graha Yuddha, in this case it lifts it up beyond where it might be expected to go. Both planets also do well together in the Navamsha. In the concert birth chart they reside in Jyestha nakshatra, ruled by Mercury, who is well placed in Capricorn in an angular house (the 7th house of the birth chart). From Cancer Ascendant Mercury also rules the 3rd house, which is associated with music.

Repeating this theme of gaining success after a disadvantageous start (public opinion challenging the premise of the concert, even if mightily curious to attend), the Navamsha chart contains three debilitated planets (Sun, Venus, Jupiter) and one exalted planet (Mars). Navamsha Sun debilitated in Libra is corrected by Venus in an angular house from Navamsha Moon, thus Neecha Bhanga Raja yoga. Navamsha Venus debilitated in Virgo is corrected by Jupiter in a kendra from the Navamsha Ascendant, thus Neecha Bhanga Raja yoga. Navamsha Jupiter debilited in Capricorn is corrected by Mars also in Capricorn, as mentioned, thus also Neecha Bhanga Raja yoga. This yoga often refers to a person or a situation (as in this case: an event chart) which starts out with disadvantages and becomes even stronger somehow, possibly because of the initial uphill conditions and determination to triumph over the odds.

Cancer is associated with families, and Paul Whiteman was at times called “A Great Big Family Man,” a double entendre, as he was a big man size-wise and he was devoted to his many fine musicians all across the country. He encouraged them and persuaded many of them to leave their jobs in symphony orchestras, in part because he knew their quality and could pay them far more for it. He and his band moved to New York City in 1918 and began recording with the Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA Victor) in 1920, giving Whiteman and his band national prominence. He was the best known dance band leader in the 1920s in the U.S., with a decline only by the late 1930s. Whiteman went on to bring many musicians to national prominence, including George Gershwin, and also singers Bing Crosby and Dinah Shore. He worked with many black musicians behind the scenes, but due to the segregation era his managers vetoed his working with them publicly. (See Whiteman’s birth chart further below.)

Click here for a brief review on how to read the South Indian charts.

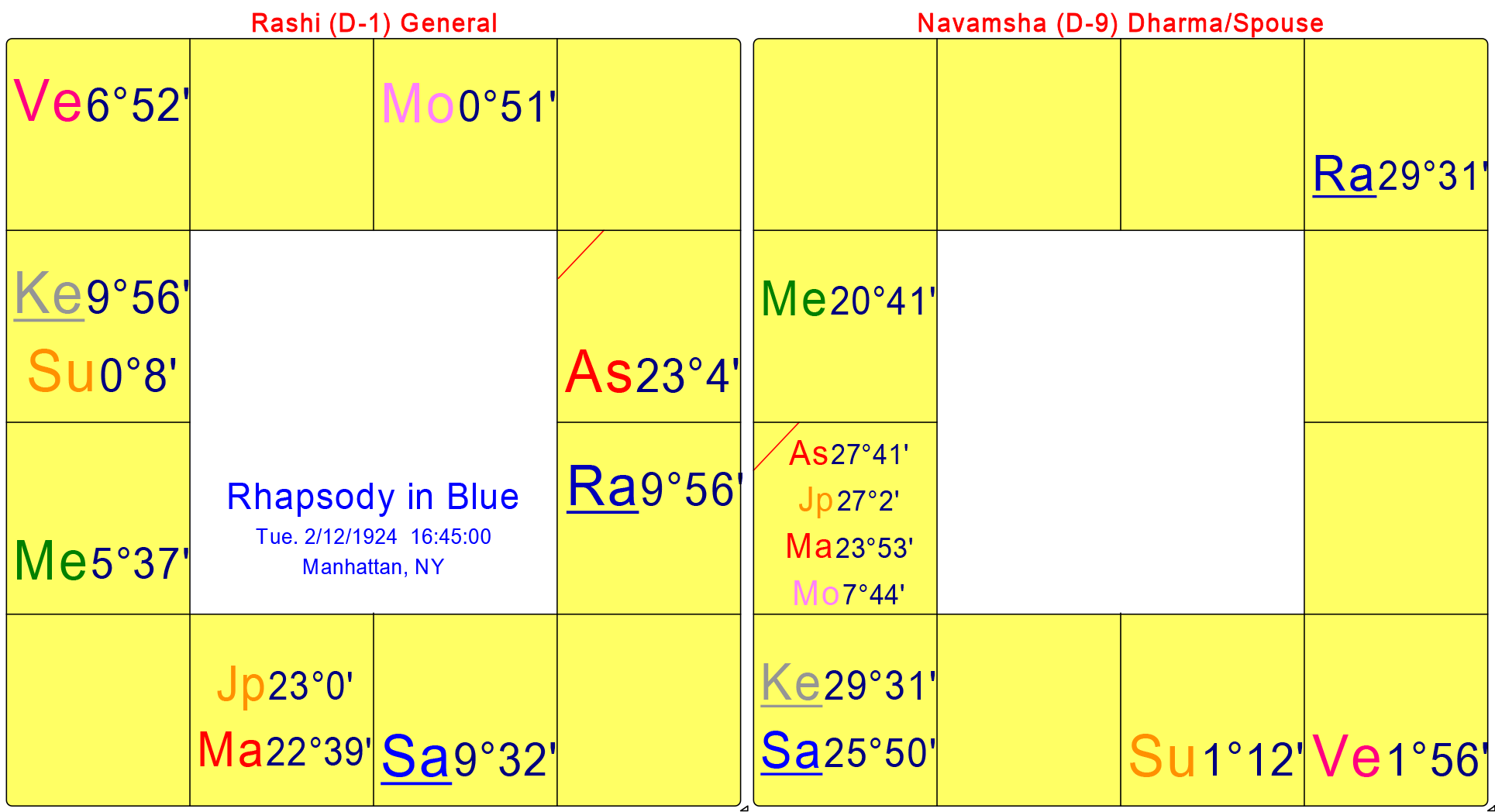

SOURCE: Tuesday, Feb. 12, 1924, 4:45 pm EST, Manhattan, NY, USA. This time for the exact moment when Rhapsody in Blue was performed at its World premiere concert is my speculative rectification, based on numerous factors, including a start time estimated to be sometime between 3:01 and 3:15 pm. The scheduled and announced start time was 3:00 pm, Feb. 12, 1924, as given in the previous chart. Gershwin’s piece was 25th on a program of 26 individual pieces. Music critics reported that the audience responded to it with “tumultuous applause” and demanded three curtain calls. Rhapsody in Blue is estimated to have lasted ca. 16 minutes. The next and last piece was Edward Elgar’s 1921 march Pomp and Circumstance (the one most often played at graduation ceremonies). A recent recording of that piece cites its duration as 8 min. 47 secs. Paul Whiteman, in his 1926 autobiography Jazz (co-authored with Mary Margaret McBride) says: “ …[A]t half past five, on the afternoon of February 12, 1924, we took our fifth curtain call.” With a minimum of two minutes per curtain call, plus three curtain calls after Rhapsody, that makes a minimum 16 minutes of curtain calls, and does not include time to announce either piece. With 16 to 20 minutes of curtain calls after 5 pm, this fits more accurately with the duration of the last two pieces ca. 16 min. and 9 minutes, respectively, and reaching the 5th and final curtain call by ca. 5:30 pm. This differs from Joan Peyser’s account in her 1993 book The Memory of All That… (p. 83) that by 5:05 pm Gershwin’s piece had still not been played. I would disagree with this account and with Peyser’s statement that the concert began at 2:45 pm. This is based on other sources, including Whiteman himself, and the strength of the astrological chart as of 4:45 pm. Tr. Jupiter is exactly aspecting the Ascendant, further enhancing the Raja yogas described in the previous chart, and improving the Navamsha chart, whose Ascendant has moved to Capricorn, now containing Moon, Mars and Jupiter.

RHAPSODY IN BLUE – WORLD PREMIERE

Most people came to this concert because of Paul Whiteman, not George Gershwin, though he had some publicity draw – mainly as a song writer (“Swanee,” “Stairway to Paradise,” and “Do it Again”). Nevertheless, Rhapsody in Blue would turn out to be the highlight of the Aeolian Hall concert on Feb. 12, 1924. Victor Herbert’s Suite of Serenades preceded Gershwin’s on the program of 26 pieces, and though masterful, it was greeted only with polite applause. Some accounts of the event report that the audience was starting to file out, as the ventilation system in the building was broken and people were uncomfortable and impatient. The musicians and members of the audience were said to be bathed in sweat. Other reports, including from Paul Whiteman and from music critics who attended said there was enthusiastic applause after every number. So it is not clear whether conditions in the hall were becoming more and more challenging, but astrologically it is clear that Jupiter’s aspect to the Ascendant was coming closer and closer. And that was highly favorable.

Then came Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, which he originally titled An American Rhapsody. The new title was suggested by George’s brother Ira, calling attention to the E major blues themes, and also influenced by titles from a recent exhibit of paintings by James McNeill Whistler, with titles such as Nocturne in Blue and Silver, and Symphony in White.

“I had already done some work on the rhapsody. It was on the train [to Boston], with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty-bang that is often so stimulating to a composer… I frequently hear music in the very heart of noise. And there I suddenly heard—and even saw on paper—the complete construction of the rhapsody, from beginning to end. No new themes came to me, but I worked on the thematic material already in my mind, and tried to conceive the composition as a whole. I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America—of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness. By the time I reached Boston I had a definite plot of the piece, as distinguished from its actual substance. George Gershwin, quoted in Robert Kimball and Alfred Simon, The Gershwins, 1973, p. 35.

The Rhapsody’s opening clarinet glissando was considered “outrageous” by the music critics, in part because they had never heard such a thing in a concert hall, and indeed – it came as a result of reed player Ross Gorman, who at rehearsal deliberately smeared the passage from how it was written, perhaps as joke. But only a virtuoso clarinetist could have pulled off such a feat. Gershwin liked it so much he kept it in and immediately incorporated it into the piece. Gershwin’s own pianistic talents were mentioned even by critics who were more negative and questioning about the construction of the piece. And up to the present time, music experts have concurred that no one has played Rhapsody in Blue with more brilliance and verve than George Gershwin himself.

“… When Gershwin played the Rhapsody, he played it in a much freer, more open, more heavily accented and contrasted—yes, even jazz-like—style than has been achieved by subsequent performers. The two abridged recordings Gershwin and Whiteman made together of the Rhapsody have a dash and sparkle that virtually every later performance has lacked.” Ibid., p. 36.

One of the key differences between this chart for 4:45 pm and the start of the concert at 3:00 pm is of course the transiting Moon, which again repeats the themes of weakness . Though Moon in Aries is well placed in the 10th house, 10th lord Mars is defeated in Planetary War by Jupiter. When tr. Moon moves into Taurus, that weakness is replaced by sign lord Venus exalted in Pisces in the 9th house: the most fortunate house. As 4th lord in the 9th house, Venus forms a Raja yoga, and as 11th lord in the 9th house Venus forms a Dhana yoga of wealth. Though Whiteman spent $11,000 on the concert and only made $4,000 – it proved to be a shrewd investment. The concert elevated his status and had the caché of being the World Premiere of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. It was also the moment when Gershwin, the songwriter, became known as a composer. As his contemporary Irving Berlin said: “George Gershwin is the only song writer I know who became a composer.” (quoted in The Gershwin Years, by Edward Jablonski and Lawrence D. Steward, 2nd edition, 1973, p. 16).

Another way to see how the initial financial loss for Whiteman was not fateful is the condition of the Sun, lord of the 2nd house of finances. Though it resides in the 8th house with Ketu and on the eclipse axis, it is surrounded on both sides by classic benefic planets: a Shubha Kartari yoga. Mercury is in House 7 and Venus is in House 9. This is a protective yoga, and tends to fortify and shield matters of the 8th house, along with those things associated with the Sun, such as leadership. Whiteman’s leadership status was only enhanced, as was Gershwin’s in his realm.

As mentioned, by the time Rhapsody in Blue was performed, the 25th out of 26 numbers on the program, some of the audience had begun to leave because of the non-working ventilation system, according to some accounts. (Saturn in the 4th can bring some challenging conditions to the real estate.) But they watched as a confident George Gershwin strode on to the stage, sat down at the piano and gave a nod to the conductor to begin. Then came the wailing of the clarinet opening glissando. They decided to stay, hurrying back to their seats.

With the 4:45 pm chart, Jupiter has gained power, and its exact aspect to the Cancer Ascendant enhances the entire chart. In the Navamsha chart, Capricorn Ascendant contains Moon, Mars and Jupiter, another formidable Raja yoga, with Navamsha Moon having moved from its initial 6th house position (at 3:00 pm) with Saturn and Ketu. The 6th house Moon shows the many worries that were associated with this concert, along with the excitement and intense anticipation, in large part set up by Whiteman’s superior publicity sense. Jupiter is Digbala in the Navamsha Ascendant, its best angular house, and though debilitated it receives correction from now two sources: exalted Mars and Moon in the Navamsha Ascendant. This adds momentum to the three Neecha Bhanga Raja yogas in the Navamsha chart: Venus, Sun and Jupiter. These yogas in such abundance provide the possibility of elevating the status of a person or person(s) connected with this event.

The exact Jupiter aspect to the Ascendant is THE MAJOR astrological feature describing the climactic effect Gershwin’s Rhapsody would have at this juncture of the program. The potentially out-of-control energy of Mars losing a Planetary War on a Tuesday, a Mars-ruled day, is contained but not totally constrained by Jupiter. Tuesday is not the best day for a concert and is more suited to a competitive event – which this was in many ways. It was a contest to see if Whiteman and his musicians could prove the pundits wrong. Would he embarrass himself in a big way? Or would he prove something new? He strove for an educational platform to provide a learning experience if not genuine excitement about the intermingling of popular and classical music.

One headline the next day in the New York Evening Post read “Jazz Invades Aeolian Hall.” A reviewer from The Sun and the Globe confessed that he “ached to dance up and down the aisles.” Another reviewer, Olin Downes of The New York Times described the relative abandon and spontaneity of the musicians by recalling this maxim: “An Englishman entered a place as if he were its master, whereas an American entered as if he didn’t care who in blazes the master might be.” This echoes the response of conservative Russian composer Alexander Glazunov after hearing Rhapsody in Blue for the first time in 1932: “It’s part human and part animal!” (The New York Philharmonic Orchestra performed it with George Gershwin at the piano.)

Not all music critics were enthusiastic about the Feb. 1924 concert and some major critics attacked Gershwin’s work, including Lawrence Gilman, chief music critic of the New York Tribune: “Recall the most ambitious piece on yesterday’s program [Rhapsody in Blue] and weep over the lifelessness of its melody and harmony, so derivative, so stale, so inexpressive.” However, he did note Gershwin’s pianistic gifts.

On the positive side Henrietta Strauss of The Nation magazine, cited “… the spectacle of an American boy playing with extraordinary ease an original composition of terrific rhythmical difficulty and of individual power and beauty, and winning immediate recognition for his achievement.”

The public was enthralled, especially with Rhapsody in Blue. Accordingly, Whiteman scheduled repeat concerts on March 7, 1924 at Aeolian Hall and at Carnegie Hall on April 21, 1924. Following the Carnegie Hall performance, Whiteman and his orchestra went on a two-week tour to Canada as well as an extensive U.S. tour. Gershwin was the piano soloist up through June 1924, when Milton Rettenberg replaced him. The Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA Victor) noted the concert’s success and took advantage of it by recording Paul Whiteman’s orchestra numerous times in 1923 through 1928, including in June 1924 the first recorded performance of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, with Gershwin at the piano and Paul Whiteman and his Palais Royal Orchestra.

This started the piece on its way to being possibly the best known concert work of the 20th century, even if it took some decades to be fully accepted in the classical music community, helped also by graduating to a full symphony orchestra from the original jazz band score. Gershwin performed the Rhapsody for the first time in Britain in June 1925, and in 1926 Paul Whiteman and his orchestra’s successful tour all across Europe further popularized the piece. Even more worldwide attention came at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, when 84 pianists performed Rhapsody in Blue. Then on Feb. 12, 2014, at the 90th Anniversary celebration in New York City, Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks Orchestra recreated the full 1924 Aeolian Hall concert program. A rich performance history by some of the leading classical pianists and orchestras of the world are a tribute both to Gershwin’s masterpiece and also to his own pianistic gifts, with no one surpassing his own performances from the 1920s.

Click here for a brief review on how to read the South Indian charts.

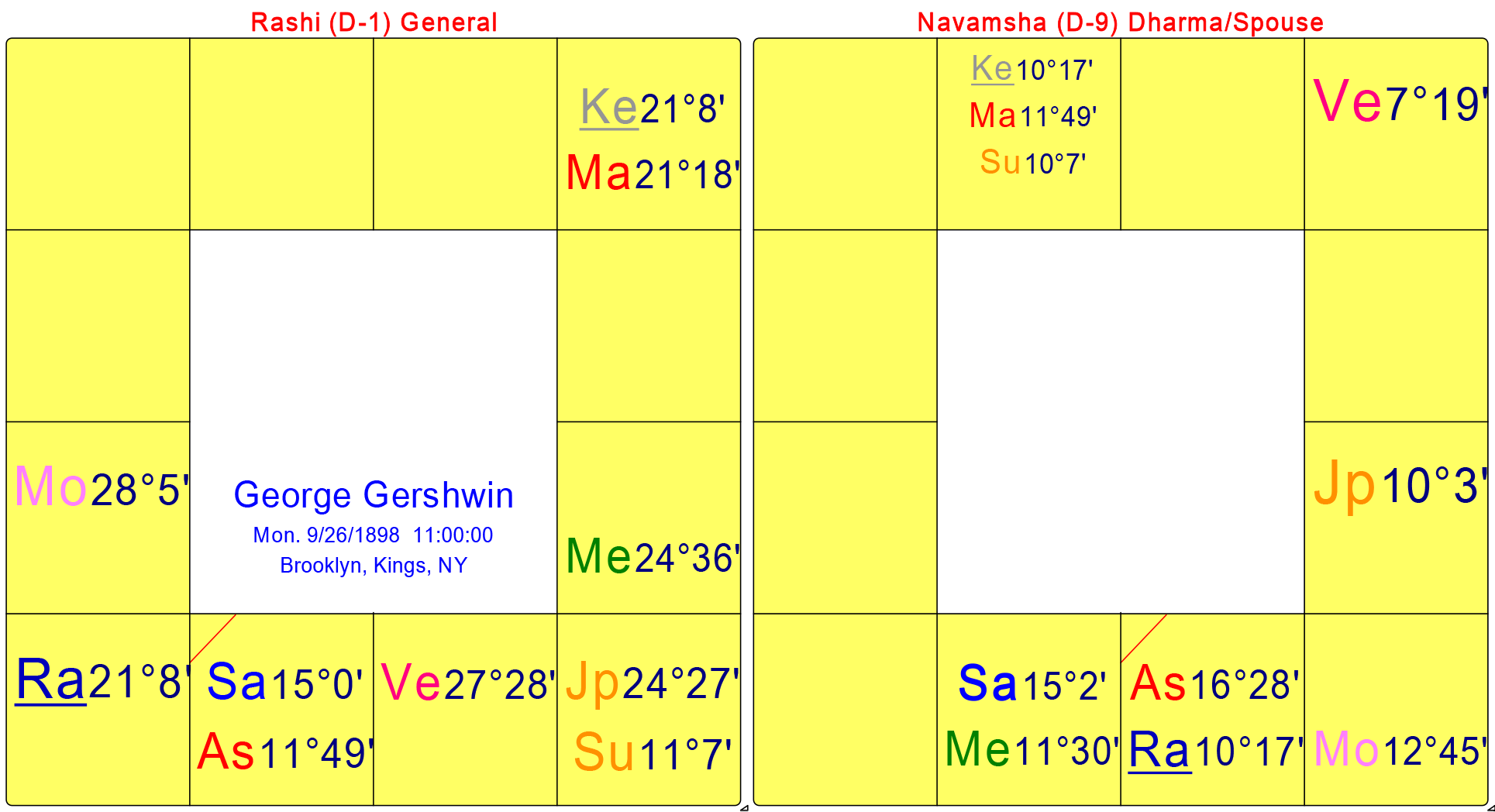

SOURCE: Monday, Sept. 26, 1898, 11:00 am EST, Brooklyn, King’s county, NY, USA. Class A data (from memory) from AstroDataBank was formerly listed as 11:00 am, which is my preferred time. Marion March quotes the time in a biography as 11:00 AM. ADB has since changed this birth time to 11:09 am (13:38 Scorpio sidereal Ascendant), though the source is not clear, and 11:09 am could have been rectified from the original 11:00 am. From ADB Source notes: Mark Edmund Jones quotes Augusta Wiley, “verified,” in Guide to Horoscope Interpretation. (Same in Sabian Symbols No.384.) Huggins in The Astrology Magazine gives 11:15 AM LMT. The time may have been rectified from an original 11:00 AM.

GERSHWIN & THE WORLD PREMIERE OF RHAPSODY IN BLUE

Prior to the Aeolian Hall concert on Feb. 12, 1924, Gershwin was known primarily as a song writer and composer of a few Broadway musicals, starting with La La Lucille in April 1919. His first major song hit was “Swanee” (1919) for which he wrote the music and Irving Caesar the lyrics. It brought Gershwin fame and riches after Al Jolson heard it and recorded it in Jan. 1920.

Gershwin first met Paul Whiteman in 1922 and worked with him and his orchestra on a Broadway show: George White’s Scandals of 1922. Gershwin’s one-act opera, Blue Monday was part of the show, but was withdrawn after opening night. The producers thought the subject matter too depressing for a vaudeville show with mostly lighter fare, but others, including Whiteman thought the 25-minute piece showed Gershwin’s ability to write what they called a “serious” work. The themes revolved around love and jealousy, with a tragic end. Reviewers mostly panned it, some very badly, but Whiteman could see in it Gershwin’s true range. Indeed, it would foreshadow later works, including his opera Porgy and Bess (1935). Whiteman admired Gershwin’s abilities and encouraged him to write an orchestral work using a jazz-derived language. Blue Monday would lead eventually to Whiteman’s commission 15 months later that became Rhapsody in Blue.

With his own watery Ascendant, Gershwin’s destiny was well-meshed with this concert chart. His birth chart contains a Mars-ruled Scorpio Ascendant, and Gershwin stood to gain from events during the year that Jupiter passed through Scorpio: Oct. 22, 1923 to Nov. 15, 1924. Fortuitously, on Nov. 1, 1923, Gershwin made his debut on the concert stage at Aeolian Hall. Canadian mezzo-soprano Eve Gautier gave A Recital of Ancient and Modern Music for Voice, consisting of classical and popular music, an innovation in concert programming for the times. Gershwin was invited to accompany her on the popular music only, with two of his songs: “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise” and “Do it Again,” both from Broadway shows. They collaborated on several more concerts in 1924, 1925, and 1926. Paul Whiteman was present at the concert and was excited with the innovation of the classical/jazz combination. Conceiving of his “Experiment in Music” concert at Aeolian Hall around that time, he booked it for Feb. 12, 1924.

Gershwin was in the 16-year Jupiter Dasha starting March 30, 1921, and in the sub-period of Jupiter-Saturn on Feb. 12, 1924. The best planets for Scorpio Ascendant are Sun, Moon and Jupiter. They also have high status as Nadi yogakarakas, and work well here: Natal Jupiter contacts the Sun and aspects the Moon in the 3rd house of music. Thus, Jupiter Dasha is undoubtedly his best life-time Dasha. And while Jupiter is Dasha lord, the transits of Jupiter become extremely important. So we see the many multiplying benefits tr. Jupiter in Scorpio would bring Gershwin.

Another resonance to this concert chart and its tight Mars-Jupiter conjunction comes from Gershwin’s Nadi yoga between Mars and Jupiter: Mars is in Jupiter-ruled Punarvasu nakshatra, and Jupiter is in Mars-ruled Chitra nakshatra. This gives the two planets a great deal of close interaction in the chart and in the life. They also aspect each other: Mars aspects Jupiter in the birth chart, and Jupiter aspects Mars in the Navamsha chart. Since Mars is Ascendant lord, Jupiter gives an expansive, energizing effect to this already very active Mars. Gershwin’s ongoing nervous, electrical energy and his non-stop work and play schedule made him highly productive, but also may have caused mental and physical burnout. However, during Jupiter Dasha, he was able to go full throttle, and indeed he did.

Gershwin’s destiny for fame and fortune is already contained within the birth chart. He benefits from having these yogas: 1) Amala yoga: A classic benefic is in the 10th house from natal Moon or Ascendant. Ideally the benefic should not be afflicted by a malefic associated with it or aspecting it. Gershwin has this yoga both from the Ascendant (Mercury) and the Moon (Venus). 2) Maha Parivartana yoga: The Sun in Virgo in the 11th house is in mutual exchange with Mercury in Leo in the 10th house, benefiting his status, career, and moneys made from his career. Fortifying this yoga are two other very positive yogas: 3) Shubha Kartari yoga: Classic benefic planets straddle the 11th house Sun and Jupiter, benefiting the affairs of the 11th house, along with Sun and Jupiter. Next is 4) Ubhayachari yoga: Planets are situated in the 12th and 1st houses from the Sun, supporting the Sun and reiterating the theme of Gershwin’s large network of friends and supporters. Fortunately, Jupiter is two degrees beyond the classical range of combustion and benefits vicariously from the Sun’s Parivartana yoga with Mercury.

Less fortunate yogas include: 1) the Arishta yoga: Ascendant lord Mars is in the 8th house, a Dusthana house, with classic malefic Ketu opposite Rahu. He died at age 38, just a few months into his Saturn Dasha; and 2) Kemadruma Bhanga yoga: Moon with no physical planets on either side of it, but corrected twice, by an angular planet from the Moon (Venus, also creating the Amala yoga) and by an aspect from benefic Jupiter.

Against the larger planetary backdrop and coinciding within five months of the start of his 16-year Jupiter Dasha (March 30, 1921), Gershwin’s destiny benefited from a Jupiter return to its natal sign and house in late August 1921, and from the 20-year Jupiter-Saturn conjunction cycle. A JU-SA conjunction occurred at 3:49 Virgo on Sept. 9, 1921 (Uttara Phalguni nakshatra). This conjunction occurred in his 11th house with natal Sun and Jupiter in Virgo already participating in several auspicious yogas. Natal Sun is at 11:07 Virgo, close to exactly on the 11th house cusp from the Ascendant at 11:49 Scorpio. With the 11th house defined by financial gains, large networks of friends and also elder brother, we see the huge importance of George’s ever-widening social network as well as his older brother Ira Gershwin. Ira was his biggest supporter within the family and became his business partner and chief lyricist/collaborator after 1924. This in turn benefited the well-being and financial fortunes of the entire extended Gershwin family. Not only is 11th house the older sibling but Mars is karaka of sibling, as well as being lord of Scorpio Ascendant.

Click here for a brief review on how to read the South Indian charts.

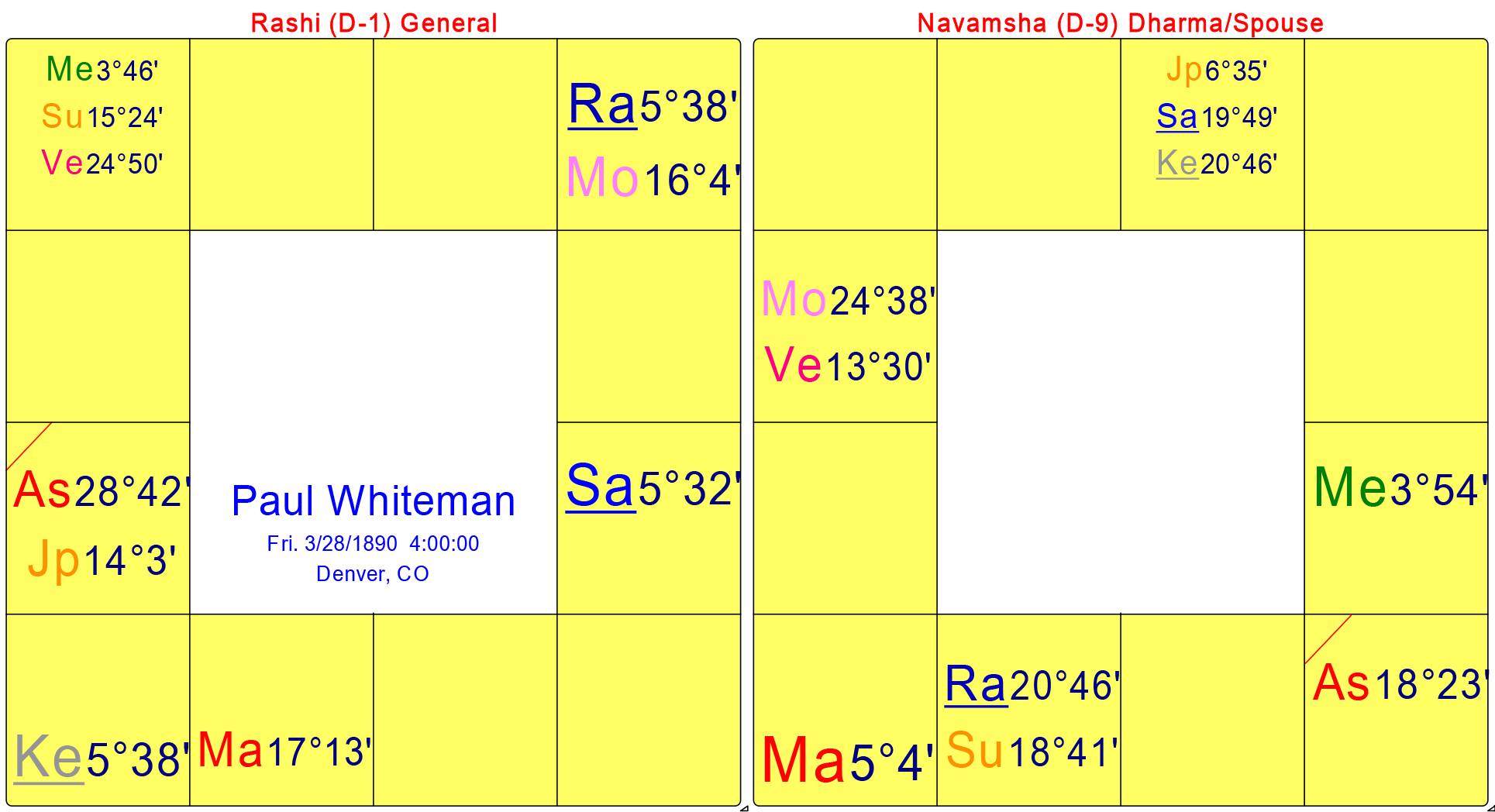

SOURCE: Friday, March 28, 1890, 4:00 am MST, Denver, Colorado, USA. Class C Data from AstroDataBank. (Class C = Original source unknown).

Even with Class C data, this chart is notable for repeating many of the patterns of the concert chart for Feb. 12, 1924: Mars in Scorpio, a prominent Jupiter, and Venus in Pisces. As with the concert chart, Whiteman has several planets in watery signs: in this case four planets: Mars in Scorpio, and Mercury, Sun and Venus in Pisces. Venus is within 2 degrees of her maximum exaltation degree at 27:00 Pisces.

Jupiter’s expansive influence makes this Capricorn Ascendant chart a real possibility. Aside from his large physical stature (and he grew more rotund with the years), Whiteman made this statement about his intentions for the Feb. 12, 1924 concert, An Experiment in Music: “I intend… to sketch, musically, from the beginning of American history, the development of our emotional resources which have led us to the characteristic American music of today.” (Edward Jablonski, Gershwin: A Biography, 1987, p. 62)

His planets in Scorpio (Mars), Capricorn (Jupiter) and Pisces (Mercury, Sun, and Venus) resonate well with both the concert chart and with Gershwin’s chart. His natal Moon at 16:04 Gemini is close to Gershwin’s Ascendant lord Mars at 21:18 Gemini, both on the eclipse axis. Note too that Whiteman has two debilitated planets (Mercury and Jupiter, both Neecha Bhanga Raja yoga), one exalted planet (Venus), and a planet in its own sign, swakshetra (Mars), all of which add strength to the chart. The debilitated condition of both natal Mercury and Jupiter continues the themes from the 3 pm concert Navamsha chart of rising up out of some initial disadvantages.

If his Ascendant is correct, at 28:42 Capricorn (Dhanishta nakshatra), it is very close to Gershwin’s natal Moon at 28:05 Capricorn. This would support a close emotional and/or intuitive bond between them. Both men also had marital issues, a characteristic of Dhanishta nakshatra: Whiteman was married four times, and Gershwin had numerous romantic connections, usually with unavailable married women. In any case, there was a close link between the two men that served to make the Aeolian Hall concert of Feb. 12, 1924 one of the major concert events of the 20th century.

*******

SELECTED REFERENCES

Books

- Jablonski, Edward, Gershwin: A Biography, 1987.

- Jablonski, Edward & Lawrence D. Stewart, The Gershwin Years, 2nd edition, 1973.

- Kimball, Robert and Albert Simon, The Gershwins, 1973.

- Peyser, Joan, The Memory of All That: The Life of George Gershwin, 1993.

- Pollack, Howard, George Gershwin: His Life and Work, 2006.

Links

- http://bixbeiderbecke.com/ReviewRecreationAeolianHallConcert.html

- https://edithhathaway.com/graha-yuddha-testing-the-parameters-of-astrology-and-astronomy/#more-88

- http://www.gracyk.com/whiteman.shtml

- http://www.jerryjazzmusician.com/2016/08/revisiting-an-experiment-in-modern-music/

- http://www.nytimes.com/1987/02/15/arts/recordings-the-whiteman-concert-of-1924-lives-on.html

[This article also appears in the Feb. 2017 issue of Astrologic magazine, an on-line magazine.]

Copyright © 2017 by Edith Hathaway. All rights reserved.